One of the most succinct definitions of conscious leadership that I’ve seen comes from the Conscious Leadership Group (CLG). It was made clearer to me in a recent email exchange with Jim Dethmer, one of the three principals of CLG. He writes: “We define leadership as taking responsibility for the influence you are having in the world.”

I love succinctness so this definition appeals to me. But does responsibility mean the same thing for me as it does for someone else? As I ponder this question, I recall the times in recent years when I have encountered this word, almost exclusively in the context of creating a sustainable, just and fulfilling world.

When I published The Great Growing Up, we decided on the subtitle of “Being Responsible for Humanity’s Future.” My original subtitle was “Taking Responsibility for Humanity’s Future” and my friend Bill Liao happened to be in town visiting from Ireland. He suggested that “being responsible” had a deeper personal commitment than “taking responsibility” which could be seen as more conceptual or removed from the personal to some degree. I agreed, so we changed the wording.

I ran this past Dethmer in our recent email exchange and he wrote back: “I like the idea of being responsible but one of the ideas we stand for is that responsibility is something that a leader takes, it is an active choice.”

So we see that even people with aligned intentions can have different perspectives.

As the corporate social responsibility (CSR) movement was gaining traction fifty or sixty years ago, a good number of traditional business people were confused about the word. Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman had previously made a strong case that market fundamentalists love to cite: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits…”

This was not the meaning of social responsibility that more socially conscious thinkers had in mind when they founded Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) in 1992. Their meaning of the word related to environmental sustainability and they urged companies to focus on the impact they had on planet Earth. Around the same time, the World Business Academy (WBA) was founded by a group of business people who adapted a broader concept of social responsibility. In 1991, while I was serving as its managing director, we approved a logo design and tagline still in use today: “Taking Responsibility for the Whole.”

This distinguishes social responsibility from Friedman’s focus on only shareholders (a small group or “a part”) to the larger group or “the whole” – another way of saying responsible for the common good – that’s everyone’s common good.

When one is committed to the common good, one cannot in good conscience make a profit while polluting the environment, profiteering on human suffering, or gaining market advantages by supporting inhumane abuses.

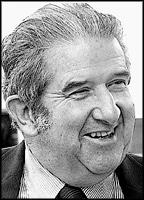

Visionary social scientist Willis Harman (pictured at left), the founder of the WBA, saw the wisdom in this wider interpretation of responsibility. Harman could see the folly in thinking that any one group in this highly-connected world could feel secure while other groups did not; that some could feel safe and have all their basic needs met while others were starving and under threat. Harman was one of the first people I knew who realized that all human beings were part of the same “whole” – and viewed the idea that people are separate and not interconnected as a myth. A systems thinker, one of the analogies he shared more than once was between the human body and the entire human species. “You don’t hear a kidney complaining about the heart Willis Harman (1918-1997) getting more than its fair share of blood, do you?” he would quip. Like parts of the body, he saw that each of us has a role to perform and we are all part of the same organism.

Visionary social scientist Willis Harman (pictured at left), the founder of the WBA, saw the wisdom in this wider interpretation of responsibility. Harman could see the folly in thinking that any one group in this highly-connected world could feel secure while other groups did not; that some could feel safe and have all their basic needs met while others were starving and under threat. Harman was one of the first people I knew who realized that all human beings were part of the same “whole” – and viewed the idea that people are separate and not interconnected as a myth. A systems thinker, one of the analogies he shared more than once was between the human body and the entire human species. “You don’t hear a kidney complaining about the heart Willis Harman (1918-1997) getting more than its fair share of blood, do you?” he would quip. Like parts of the body, he saw that each of us has a role to perform and we are all part of the same organism.

Social responsibility from this perspective – one I happen to share – means keeping the common good in the forefront, not allowing any one part or facet to get so greedy or overconsuming that it jeopardizes the whole. This will take some serious rethinking about our social structures and ambitious reformations which will require much individual and collective courage to implement. Harman says it well in the short video below.