August 2009

Those of us who have been writing and talking about organizational and social transformation for some time continue to encounter resistance to change everywhere we look. It shows up in families, companies, governments and societies. Often, even on those rare occasions when meaningful change does take place, it often doesn’t last as the old ways return and business as usual is the default culture.

As a systems thinking scholar I see it from the system/culture perspective which is fine for an academic take on it. But where does it show up in individual action? What is the forensic of the resistance, the fingerprints of sabotage or the lineage of rationality that prevents lasting meaningful change from occurring in complex cultures, be they familial, organizational, communal or social?

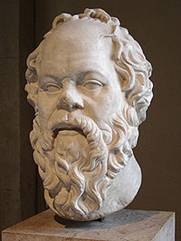

Socrates defined the status quo as the “vested interests” but isn’t this a little too simplistic? Lynn Margulis, author of Symbiotic Planet, writes how as a species we cling to the “familiar, comforting conformities of the mainstream” and avoid anything that causes “discomfort about our culture’s sacred norms.

Recently I have been reading Nassim Taleb’s The Black Swan. He makes a compelling case for how we humans have such disdain for the abstractions of complexity that we rush to create explanations about aberrant events as if to create our own “comforting conformities” that allow us to return to the familiar. Thus we minimize that period of discomfort that usually arises when something like the 9-11 terrorists attacks, the 2008 economic crash or any other it-wasn’t-supposed-to-happen-event happens. These Black Swan events often come about through a series of random occurrences in a perfect storm of circumstances. Linear thinking alone cannot fathom these Black Swans yet we steadfastly refuse to embrace these types of abstractions.

Taleb writes, “We harbor a crippling dislike for the abstract….our emotional apparatus is designed for linear causality….Out of sight, out of mind: we harbor a natural, even physical, scorn for the abstract.”

As I read these passages, something stirs within me, akin to seeing a face I think I’ve seen before but can’t place it; a zone between intuition and faint memory but just enough stirring that I stick with it. As I mull this over, something starts to take form as a thought. There is a connection between this disdain for the abstract and our attachment to linear causality. This is where we are at odds with nature, the universe. The world is abstract, causality is abstract, science is abstract and if we insist on seeing everything through the lens of linearity we are doomed. We are out of sync with nature. This is groupthink at the species level.

Then I feel an audacity rear up in me. Taleb is wrong about one thing. Our emotional apparatus is not designed for linear causality. Our emotions are quite competent in engaging the complex and the abstract. It is our minds that “scorn,” “dislike,” “harbor” and decide what is “sacred” – not our hearts!

Our minds would have us be prisoners of the past rather than leap into the unfamiliar. Our minds like everything spelled out neatly and rationally and fully explained, even if the explanation isn’t correct. Better it be rational and linear than accurate. Our minds are happy as long as we can explain things, and things “make sense.”

So where does this leave me in my inquiry? Are we doomed to experiencing only the “familiar, comforting conformities of the mainstream” as Margulis states? Are we really designed only for linearity? Both of these observations imply we are hard-wired. But human beings can change. With enough willingness to venture into the unfamiliar and perhaps enough pending doom could motivate us make us to take a chance. So it comes down to a question of willingness, not capacity. Will people be willing to engage the unfamiliar, to be more innocent and less knowing, to feel less certain and have things make less sense? Will people seek sufficient knowledge of the newly engaged domains of abstractions and complexities – fields we have been generally avoiding all our lives?

Now how does this play out in individual action? Instead of jumping from one lily pad of certainly to another, perhaps we can wade into the water of uncertainty and suspend explanation until a more systemic understanding of the goings on are fully explored. Instead of rushing to conclusions in the rapid search for explanation, one searches for the meaning in the context of what matters.

This will happen when meaning becomes more important than explanation, when wisdom trumps information, when inquiry is valued more than rushing to conclusions. This requires postponing immediate gratification of the plausible explanation in exchange for gaining a greater comprehension of the way things work in the world. Thus we are equipped to better function in cooperation with nature. I think they call this maturity.