Oct 2013

Some people may think of fantasies as really fantastic dreams, perhaps dreams that are less likely to come true than the ordinary ones. We can dream about making the varsity football team, or getting asked to the prom by a really popular student, or receiving the promotion at work, or finding that “dream house” for our first home. These are dreams we believe we can achieve – situations that have some chance of occurring. While they may be unlikely or improbable, they remain possible.

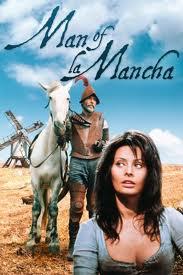

Peter O’Toole as Don Quixote and Sophia Loren as Dulcinea

But there are the “impossible dreams” Don Quixote sings about in “The Man of La Mancha.” These are fantasies without hope, figments of our imagination that entertain us, “mind candy,” to help us endure life’s harsh realities and offer consolations in times of hopelessness and despair. Like becoming President or sleeping with a movie star, a fantasy can also be a place solely in one’s imagination which is never really expected to happen.

THE DISTINCTION

About thirty years ago, one of my teachers suggested that the primary distinction between a fantasy and a dream was that the person with the fantasy never really expected it to manifest in real life. But the fantasy served them by providing a consolation that “kept them going” when things got tough. Their fantasy provided them with an anesthetic – an artificial experience which took the place of the real thing.

These “fanta-seers” find solace in the fantasy while their minds rationalize how grand their fantasy is. Many of these people expect to be admired and respected, not for their achievements or the results they produce, but for the magnificence of their fantasies. The more noble their cause, the more they expect to be praised, regardless of the likelihood of their manifesting it.

Dysfunctional organizations are known to indulge in fantasies to mask or even justify behavior that most healthy organizations would never tolerate. But their dysfunctions – such as under performance, failed objectives or workplace incivility – are excused because of the magnificent fantasies they envision. One often sees this in organizations engaged in humanitarian missions.

I’d like to draw upon this distinction between fantasy (something that will never happen) and dream (something that has intention and a chance of turning into reality) to explore my own experiences of the two.

I’ve had my own fantasies and taken lots of comfort in them. They became my best friends – visions to take to bed with me, wondrous affirmations to proclaim, rationale for continuing to tilt at windmills, and comforters to ward off the chill of reality. My fantasy world allowed me to avoid many of life’s harsher calls – including personal responsibility, accountability, and self-sufficiency.

But my fantasies also distracted me from my own authentic gifts and talents, and from acknowledging my own power and self-respect. So much of my attention was projected “out there” to my wondrous imaginings that I didn’t see how uniquely I could show up in the world, right here where I am.

I soon saw the difference between having fantasies and having dreams was neither in the words nor in the probabilities of their coming true. The main difference was in how I held them in my own consciousness – as something I was committed to bringing forth and creating, or as an idealistic illusion that provided me with some artificial solace – a hero in my own movie!

TRAPPED IN THEIR OWN JAIL CELLS

From what I’ve seen, in myself and others, people steeped in this illusion begin to confuse their fantasies with who they are. They become so identified with their fantasies that their identity merges with the ideals to which they claim to aspire, and their self-image gets confused with the illusion. When our identities get confused with emotional attachments in this manner, any perceived threat to the fantasy to which we are attached becomes a threat to us personally.

When I was holding onto my fantasies, I was trapped. While I would apparently be striving to bring about this magnificent vision, my egoic mind knew that such manifestation would be a threat to my self-image. Manifesting the fantasy would eliminate my reason for living, the very thing that gave my ego solace and consolation. If my fantasy did actually materialize, what would become of me – the me who had sacrificed so much of myself in identifying with this ideal?

My ego would be more comfortable keeping the fantasy alive as part of my self-image even if it meant sabotaging what I claimed I was trying to accomplish! What a paradox!

This dynamic, as crazy as it may sound, is the stuff of which martyrs are made. I define a martyr as “a victim in drag.” Victims are easy to spot and few of us enjoy being around them (except they might make us feel more fortunate or in control). Martyrs have a victim’s mindset but they can also come across as more functional. In their core, they are quiet sufferers, committed to lives of unfulfilled grandiosity, struggling to achieve unattainable goals, enrolling others in their struggle and evoking sympathy and guilt from their friends and acquaintances.

Think of someone you know who lives in a fantasy – apparently striving for some far off ideal but making no notable progress. Their conversations are filled with activities and so-called “progress reports” but the goal line is no closer than the last time you talked with them. You ask them how they are and they tell you how their project is doing, again confusing themselves with their so-called work.

To be continued.

[End of Part One: Next month’s continuation of this opinion piece starts with “The Impact Martyrs Have on Others”]